Sharm el-Sheikh: Before the Blasts

23/07/2005

La caduta del muro di Berlino, un equivoco mediatico

09/11/2007Mrs. Anna is the woman who works at the bar close to my house. She is from Ukraine and has been living and working abroad since 1980. She is 54-years old and sometimes talks about her country. She has big hands because she has done a lot of jobs. “When I was young,” she used to joke, “in my country there was the equality of sexes: women were like men, we did the same heavy jobs!”

Last autumn she went back to Ukraine. I met her some days before she left for Kiev, the capital of Ukraine, and she showed me her orange scarf. “I’m going to Kiev,” Anna said. “I have to go home for the revolution.”

I was a little bit perplexed. When I returned home and watched TV, the newsman was talking about a far away country, Ukraine, and about a place — Independence Square — where thousands of people, dressed in orange clothes, were going and protesting in sub-zero temperatures for the biggest peaceful demonstration that Ukrainian history remembers: the Orange Revolution.

I traveled to Ukraine a year after those dramatic events of the autumn 2004. Mrs. Anna still works at the bar close to my house and she introduced me to Tanja, her daughter who studies in Kiev.

I meet her and ask her to be my guide. Tanja is 20-years-old and sometimes goes abroad to meet her mother. She has wonderful blond hair and painted nails, she keeps in fashion, has got a trendy mobile phone and speaks English very well.

I can see how different Anna’s old world is from her daughter’s. “One generation, but it seems one hundred years has past!” I think.

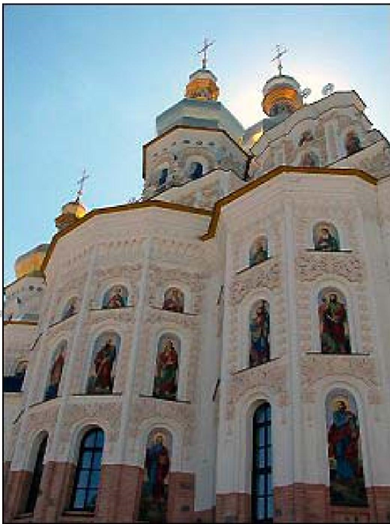

We walk between wonderful parks and gold Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches, many of them re-built during the last 20 years because they were destroyed during the Revolution of 1917 (since Communists believed that God didn’t exist, churches were not necessary) and during the Second World War.

We arrive at the beach of the Dnipro, the third largest river in Europe which divides Kiev in two parts, where I see people swimming.

In 1986, an explosion destroyed part of the nuclear complex at Chernobyl, a little and still-unknown city in the north of Ukraine (but in those years part of the USSR). Vast areas of eastern and northern Europe were contaminated by the radioactive fallout; large quantities of radioactive cesium were carried into the Dnipro and ultimately deposited in the sediment of the water reservoirs. “Nowadays, we cannot know what the reactions are on human bodies,” Tanja answers to my questions. “However a lot of people still swim in radioactive waters. They don’t worry, they are fatalists.”

“What about the Orange Revolution?” I ask her as we resume walking.

She smiles and answers: “Ten years under ex-president Leonid Kuchma left an enormous gap between rich and poor and Ukraine became one of the most corrupt countries in the world. Between 1994 and 2004, privatization placed lucrative companies in the hands of a few rich men. So, after a disputed election, during which he and his favored presidential candidate, Viktor Yanukovych, where accused to electoral malpractices, the reformist Prime Minister Viktor Yushchenko, who some parliamentary communists and oligarchs conspired to sack in 2001, drove the peaceful revolution.”

Interesting, but I want to know more. So I ask if no one said anything about the corruption.

“The Ukrainian media were not free in the past. There were some scandals.” She continues, “In 2000 the journalist Grygory Gongadze was killed and an audiotape where a voice very similar to Kuchma can be heard pointed to the alleged involvement of the ex-president, but he never heeded calls from the public to resign.

“But during the revolution, those days were signaled from the courage of another girl, Natalya Dymytruk, a sign-language interpreter on the TV channel Ut-1, who refused to translate the words of the government candidate Viktor Yanukovich. She said in one of the most popular TV broadcasts of the country, ‘I’m disappointed to be translating these lies, don’t believe the results they have announced. And this is probably my last day in this job, so goodbye.’ Her rebellion was a shock for the entire nation and for the media world, but by that night Ukrainian viewers were receiving the most free and fair news broadcasts in the nation’s history.”

A year after those events, life in Kiev is back to normal. On the stalls, some orange gadgets recall those months. We walk along the big streets through elegant buildings and wonderful churches and stop close to a group of people who are handing out some papers with something written in Cyrillic. I ask Tanja if she can translate the paper. She smiles and reads, “The revolution is not finished.”

So she explains that people are a little bit disenchanted after a year of waiting. They wanted fast changes, but fast changes are impossible. The ideas of revolution are ideas of a new country, a new state without corruption and those changes come slowly, it takes a change of habits and mentality. Tanja talks always about her mother Anna, whom she loves. “She made a lot of sacrifices in her life. Her life was so different from mine. I want this country to change for her, too.”

While she is talking, some young people give us another paper. It’s an advertisement for a global mobile phone company. It used the enthusiasm of the people to launch a new advertising campaign, saying, “The feature’s bright, the future’s orange. A sign of the times.”

But Tanja is an optimist about the future. She says the revolution is now, it’s here, it’s always, with or without this government. I smile, but maybe I don’t understand her words.

We arrive in Independence Square. I ask her to take a picture of me. It’s 8:30 p.m. The sun is going behind the palaces, painting the sky red and blue. People drink and smile. Tanja looks at me, clicks the camera and says: “Smile, you are inside a revolution.”

Published on Ohmynews International (31.01.2006)